Original historical research from the students of Stratford Academy, Macon, Georgia.

Wednesday, March 4, 2015

Tuesday, March 3, 2015

Bell South

Bell South Telephone Company

Macon, Ga

Henry Grady’s New South program encapsulated the idea of industrial growth and development throughout the south. Henry Grady believed that by increasing industry in the region, the south’s postwar social and economic problems could be solved.

The Bell South Telephone Company, started by Alexander Graham Bell in the late 1800’s, contributed the kind of industrial development that Henry Grady vied so strongly for. As a company extending throughout the south, by the early twentieth century Bell South had lines connecting nearly all towns in every southern gulf state. Extending telephone lines allowed people across different states to communicate more easily and produced opportunities for companies to broaden their businesses. The installation of these lines, however, required many laborers to work dangerous jobs that sometimes led to death. Even though the working conditions were sometimes brutal, we think Bell South Telephone Company was mostly advantageous to the south, as it facilitated widespread economic development, allowed social mobility and resulted in the gradual decline of severe inequality that had previously plagued the south.

| In 1898, Macon implemented a new system from the Southern Bell Telephone Company called a switchboard. The switchboard was state-of-the-art technology at the time. It devised a system that improved connections and limited operator interaction, bringing communication to Macon with ease. The switchboard and the improvements it brought to the lines illuminated growth and development. In 1898, the Southern Bell company was improving Macon’s telephone system and adding the best telephone operating program in the country. In this way, Macon itself was growing economically as more people were able to buy lines as the city expanded as a whole. The Southern Bell company was also developing economically as the company’s updating and enhancing of its systems brought about expansion of the business. |

In 1897, Southern Bell and other telephone companies were extending telephone connections to major cities across the south. Macon was being persuaded to participate in the widespread connection of southern lines. These extensive communications were significant to the economic development of the south because they allowed corporations to span across much larger areas, thus attracting a larger field of business. Southern Bell Company recognized the importance and value of these connections, but they refused to participate after failing to buy out the Valdosta Company. This type of attempt to buy out smaller, more regional corporations and consolidate them into a much larger, more extensive business was very typical in the late 19th century because it allowed profits to be concentrated in one corporation instead of scattered throughout the local organizations.

In the early 1900’s, the Southern Bell Telephone Company began stretching lines farther than ever before in Macon. In addition to the many lines running throughout the city, the company also started building lines that reached the rural parts of Macon. These additions were made for the benefit of southern farmers outside of the city. With the lines, farmers could increase their commercial business and production by communicating with buyers at a larger distance. This communication developed the businesses of farmers and allowed them to grow economically. With these economic benefits, greater social mobility and equality were also brought to farmers. Farmers could more easily be in contact with those inside the city or farther away. They were no longer isolated from the industrial hub of the city and with their growing businesses they had the opportunity to better their social positions in the community.

| Men on the phone lines worked in very dangerous conditions, working unprotected with electricity and working up on tall poles without equipment. There were many injuries that resulted from phone line injuries and many workers lost their jobs because they had no insurance. |

Works Cited:

“An Improved System.”Macon Telegraph [Macon] 11 Oct. 1898: 8. Georgia Historic

Newspapers. Web. 19 Feb. 2015.

<http://telegraph.galileo.usg.edu/telegraph/view?docId=news/mdt1898/mdt1898-

2456.xml&query=Southern bell Telephone company&brand=telegraph-brand>.

“Good Wires to Reach.” Macon Telegraph. [Macon] 10 June 1897: 6. Georgia Historic

Newspapers. Web. 13 Feb. 2015.

1483.xml&query=southern%20telephone&brand=telegraph-brand>

“Lightning Deals Death to Workmen.” Macon Telegraph. [Macon] 8 July 1902: 1. Georgia Historic

“Lightning Deals Death to Workmen.” Macon Telegraph. [Macon] 8 July 1902: 1. Georgia Historic

Newspapers. Web.16 Feb. 2015.

<http://telegraph.galileo.usg.edu/telegraph/view?docId=news/mdt1902/mdt1902-

<http://telegraph.galileo.usg.edu/telegraph/view?docId=news/mdt1902/mdt1902-

0065.xml&query=southern%20bell%20new%20lines&brand=telegraph-brand>.

Man on Telephone Pole. Digital image. Google. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.

“The New Directories of Telephone Subscribers.” Macon Telegraph [Macon] 24 Dec.

Man on Telephone Pole. Digital image. Google. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.

“The New Directories of Telephone Subscribers.” Macon Telegraph [Macon] 24 Dec.

1908.8.Georgia Historic Newspapers. Web. 17 Feb. 2015.

Women operating lines. Digital image. Google. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.

Macon Cotton Mills US History 11-1

Project By: Carter C. Dylan Q. Caroline R. Mariam A. Mackenzie C. |

| http://prezi.com/d4881bvmm11v/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy&rc=ex0share |

Streetcars of Macon

|

| Old Wesleyan - A hub of transportation that is now the city's Post Office. |

Many city governments during the gilded age vied for the transition from buggies to streetcars as the common mode of inner-city transportation. Macon became home to its first line of streetcars in 1868, when the city constructed a series of tracks that stretched from the downtown business district all the way to the Georgia National Fairgrounds, which is now central city park. The tracks ran the length of the entire city and offered a safe, publically run method of transport. The trolley system had countless beneficial attributes that become even more appealing when viewing older methods that were traditionally used to mobilize goods and people. Businessmen who worked to advertise and implement the trolley system emphasized its economic superiority to the horse, a relatable concept for the general population of the time period. The gilded age saw great economic growth and prowess for the entire nation, and cities and large conurbations were experiencing rapid population increase. As more and more people settled in and around cities, it became apparent that horses and buggies were no longer the most pragmatic mode of transportation; cities needed something new, that was economically advantageous and had the ability to carry large amounts of people where they needed to go in shorter amounts of time. It was becoming increasingly important for the general population to support and utilize more fiscally responsible technologies and amenities. This was an idea that was supported by gilded age philosophy. Streetcars were an economically superior alternative to previous modes of transportation; they could be operated by clean, inexpensive electrical power. The resulting establishment of power plants around the city would effectively open up new job options for the growing middle class and benefit the local economy. To persuade the public to transition from the use of buggies, many trolley companies would offer statistical proof that over the course of a year, the cost of operating a trolley system in its entirety would be fifty percent cheaper than caring for and housing one horse for the same amount of time (“For Use of Farmers”). The implementation of the electric trolley system helped to modernize Macon’s cultural landscape, encourage economic growth and prosperity, and provide a point of social controversy concerning racism and segregation up until the time of Martin Luther King’s civil rights movement in the 1960’s.

|

| Power plants such as these were at the center of the fledgling trolley industry in Macon and also powered electric lamps throughout the city. |

Although the gilded age signaled a revolutionary wave of business for Macon and other towns in the New South, behind the glamor was a fragile economy, liable to break at any moment. For all of the new industries created, which promised quality of life improvements and convenience of access, an equal number of new resource flows were needed in great demand. Oil, coal, electricity, labor, all of these quantities provided a logistical challenge for the new aged cities of the early twentieth century. In a Macon Telegraph article from the turn of the century, a headliner warns of an impending coal shortage which could topple the cities infrastructure (“Coal”). In this specific instance, a lack of sufficient rail cars prevented coal from being adequately transported into Macon. A shutdown would trigger a complete reversal of the accomplished industrialization which characterized the age. Every streetcar, and electric lamp controlled by Macon Railway & Light was fueled by the burning of coal and no matter the economic and industrial progress made, it could be undone absent the necessary raw resources. Even if the threat of complete and permanent shutdown was relatively miniscule, the potential that ingrained conveniences could evaporate warranted headlining new stories.

|

| A view of a central street where streetcars previously ran. |

Streetcars not only changed the relationship between business and economy, but they drastically affected the social statuses of the citizens of Macon and other middle Georgia towns. In November of 1901, a bill was passed in Atlanta that requires streetcar companies to add a separate car for African Americans in an effort to establish the idea of “white-only” font cars. This type segregation was far from uncommon and, sadly, marked the beginning of a turbulent road of injustice and racism that would persist through the better half of the twentieth century. Newspapers published articles that clearly outlined the rules and regulations for the new “black cars”, as well as the ways in which different situations should be handled. The two seats in the back were left for black streetcar workers and two seats in the front were reserved for whites unless there was an over flow, in which case the two seats in the front could be filled with blacks, but only if they were not already taken by white patrons. This method of segregation was not only enforced in Georgia, but all over the south. They were dubbed Jim-Crow Laws after the black-face comedic performances that were popular during the time period. Streetcar segregation would remain a common practice until Martin Luther King instigated the civil rights movement in the 1960’s. Even though streetcars were long since replaced by modern cars during King’s time, he made an important point to desegregate them as a symbolic statement. Racism and prejudice infiltrated every area of American socio-economics and politics, and even modes of public transportation were made to comply with segregation laws.

By the conclusion of 1914, the city of Macon had over 37 miles of streetcar lines winding in and around the downtown area (“Streetcars of Macon”). The gilded age brought ideas of modernization and urban uniformity to the distressed post-war towns of the American south, opening up the doors for the coming economic, social and political progress that the twentieth century would see. As middle class families began to move away from the countryside and into larger cities and towns, urban areas become crowded and common modes of transport such as horse drawn buggies were no longer pragmatic or economical. The implementation of trolley cars advanced Middle Georgia’s economic prowess by offering a cost-efficient, uniform method of transport that used renewable energy, provided jobs for middle class Americans at new electric plants, reshaped race relations by bringing the issue of segregation into the sphere of transportation, and modernized Macon’s cultural landscape.

Streetcars and Trolleys

In the early nine-teen hundreds segregation was new to everyone. Because freed slaves had nowhere to go once freed, often times they remained working for their former masters. Still allowing African Americans to do freely what they wanted. As more and more African Americans became more natural to cities the white people were outraged by the social equality between whites and blacks. A bill that was written by Mr. Thomas J. Fedler introduced the thought of segregation between whites and blacks on streetcars. Meaning there would be separate seating for whites and separate seating for blacks. While this caused discussion between various major cities in Georgia it was exclaimed there would not be two separate streetcars for the different races, only separate seats and that, which would be too difficult for the streetcar companies to keep up with. As segregation got more serious African Americans did not have to be put in place and simply knew what they were allowed to do and they were not allowed to do.

Streetcars, espicially in Macon, Georgia became unbearably hot in the summer time. During one summer the panel were taken off the sides of streetcars creating "open streetcars". This new idea was a way to keep trolley riders happy as they commuted to their everyday stops. With the sides open it created a breeze instead of trapping the heat. Happier passengers, came to rely on the streetcar service as a convenient, comfortable mode of transportation. With increased contintment, demand for new cars increased to accomadate additional riders. This demand was an economic boom for the trolley car companies.

The Streetcars in Macon had several routes but it's main routes was down Fourth street and Cotton Avenue. A report estimated the track length to be around 20.5 miles and an inventory of 30 motor cars and 15 trail cars.

|

| The building was turned into a club named the "Power Station" |

The Macon Railway and Lighthing Company Building was a trolley buisness as well as a Light Company. The Lighting Company was run on the second and third floors while the trolleys were stored and service on the bottom floor. In 1907 the Ocmulgee Park was created just a few blocks from the Railway and Lighting building. The park drew in many visitors who were also interested in other cites around Macon. This created a large boost in buisness for the streetcars becasue they were now bringing in buisness from visitors of the Ocmulgee Park. The building was an L- shaped building and provided Macon with streetcars until it was split and sold off to other existing comapanies. The trolleys were sold to Macon Transit Authority and the Lighting Compay was sold to what is now Georgia Power.

Works Cited:

"Streetcars of Macon." Streetcars of Macon. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2015.

Historic. (n.d.): n. pag. Web."The Macon Citizen (Macon, MO), 1900-04-27 :: Macon Citizen, 1898-1901."The Macon Citizen (Macon, MO), 1900-04-27 :: Macon Citizen, 1898-1901. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2015.

Pleasant Hill Documentary

Ramsie, Robert, Mary Wilson, Ann

Works Cited:

"A Pleasant Hill Blaze." The Macon Telegraph [Macon] 18 Sept. 1895: 5. Galileo. Web. 15 Feb. 2015. <http://telegraph.galileo.usg.edu/telegraph/view?docId=news/mdt1895/mdt1895-2200.xml&query=Pleasant%20Hill&brand=telegraph-brand>.

"Ch 17 Lecture Powerpoints." Ch 17 Lecture Powerpoints. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2015.

“Colored Citizens of Pleasant Hill” Macon Telegraph [Macon] 19 June 1903: 1. Georgia

Historic Newspapers. Web. 12 February 2015.

<http://telegraph.galileo.usg.edu/telegraph/view?docId=news/mdt1903/mdt1903-

1400.xml&query=pleasant>.

Grady, Henry. "Henry Grady, "The New South" Speech." The American Civil War. Professor

Hugh Dubrulle, 2002. Web. 27 Feb. 2015. <http://www.anselm.edu/academic/history/hdubrulle/civwar/text/documents/doc54.htm

"Historic Middle Georgia." Historic Middle Georgia. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2015.

"IS Geschiedenis Dagelijkse Historische Achtergronden Bij Het Nieuws."IsGeschiedenis. N.p.,

n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2015.

“New Religion in Pleasant Hill.” Macon Telegraph [Macon] 21 July 1903: 8. Georgia Historic. Newspapers. Web. 13 Feb. 2015.

"Pour Some Out For Summer & for U.S. Laborers." Urban Scrawl. N.p., 25 Aug. 2014. Web.

03 Mar. 2015.

"Race, Matters." Collex.io. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2015.

“Several Acres of Flames.” Macon Telegraph [Macon] 23

November 1895: 1. Georgia Historic Newspapers. Web. 12 February 2015.

<http://telegraph.galileo.usg.edu/telegraph/view?docId=news/mdt1895/mdt1895-

2793.xml&query=pleasant>.

"The Work of a Woman." The Macon Telegraph [Macon] 18 Sept. 1895: 5. Galileo. Web. 15

Feb. 2015. <http://telegraph.galileo.usg.edu/telegraph/view?docId=news/mdt1895/mdt1895-2200.xml&query=Pleasant%20Hill&brand=telegraph-brand>.

"Time for Reparations?" Natural Hair Mag. N.p., 24 May 2014. Web. 03 Mar. 2015.

“To Protect Vineville.” Macon Telegraph [Macon] 28 September

1895: 1. Georgia Historic Newspapers. Web. 12 February 2015.

<http://telegraph.galileo.usg.edu/telegraph/view?docId=news/mdt1895/mdt1895-

2286.xml&query=pleasant>.

Macon Cotton Mills

Economic development, at what cost?

| (Szdfan) |

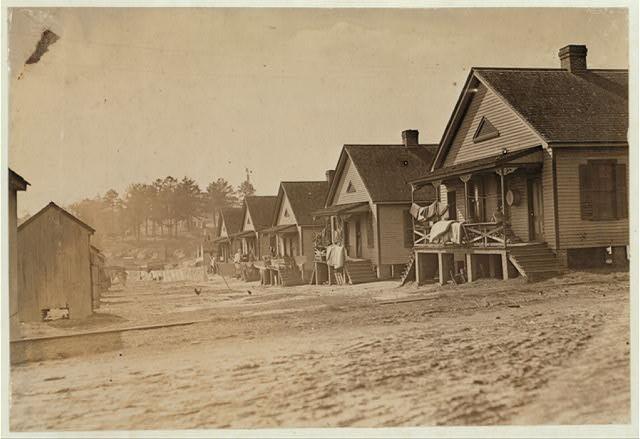

| (Bibb City) |

Henry Grady had a vision of prosperity through industrialization in the New South where there was social equality created by economic development. In the time between 1877 and 1908, the New South had an explosion of economic development in line with Grady’s vision. However, the price that was paid with this new progress was the poor working conditions in most factories and businesses. While the South was becoming more industrialized and economically connected, the factory working conditions and low wages, due to the laissez-faire policy of the government, created an economic inequality.

As you see in the picture to the left, these smoke stacks were a sign of the level of development that rose as high as the smoke stacks themselves. This was a common sign of industrialization that came hand in hand with the cotton mills of Macon, Georgia. These mills were one of the most common signs of economic development as the South now manufactured their own cotton products, not simply exporting it to the north. This is the economically independent vision for the south that Grady had hoped for. While the north was supplying capital, it was a huge step in the right direction for the south. Despite the south becoming independent, the industrialization also helped to tie the South together with the rest of the nation as internal transportation systems and communication systems, railroads and the telephone, began to spin a web through southern states. The railways especially, improved the south on an economic scale, increasing profit by cutting down transportation costs. This brought a connection of the northern and southern economies on a national scale. In an article from the Macon Telegraph there is a panic for workers in the Macon mills over wage cuts in Fall River, Massachusetts. This fright over something so far away from their actual location goes to show how interconnected the South now was with the rest of the nation, tying back to economic development (“The Fall River Cut”).

Another sign of the vast reaches of industrialization and the economic development it brought shows up in our very own town of Macon, GA. While Macon was a formidable size, it was nothing near a large city. However, in spite of this, Macon was home to and supported three large cotton mills. This exemplifies how industrialization was in the new south. In another Macon Telegraph article, the city is boasting about being able to support these mills. These people clearly supported Henry Grady’s vision for development in the New South. A second part to this article discusses how the mills hired large numbers of people, thus bringing consistent wages to these people. This constant income was a stepping stone in economic development for the South. This was a sign of an apparent shift from agriculture to industry (“Something About Macon”).

As mentioned above, the working conditions that came with industrialization were not always as fulfilling as Grady had envisioned. The Macon Telegraph, an article was published about Maj. J. F. Hanson’s speech. He was arguing to the Georgia legislature to uphold the current child labor laws, which restricted the work of children under twelve years of age. In his speech, he discussed that aside from his efforts to follow these laws, he undoubtedly had hired children below the age restriction. This was not entirely his fault, however. Families often falsified the age of their children so that they could send them to work, to supplement their abysmal wages. The parents alone working was not enough to support the family and it goes to show the downside of factory work (“Cotton Mills and Child Labor”). Along with economic struggles, the employment of children also kept them from school, depriving them of an education. The mills themselves were attracting a population of uneducated employees that required no skills to operate the machinery. Speaking of machinery, all of the women and children working at these mills were in constant danger of injury. The machines left moving parts out in the open and posed serious hazards to factory workers. These conditions came about without on the job insurance or compensation for any injuries. There was always a ready supply of workers to fill in the low skilled jobs, so mills never had to worry when it came to the dangers present for their workers.

To wrap things up, Henry Grady’s vision was ambitious but not entirely realistic within the realm of the New South. It seems like this was almost a time of trial and error for the South as they went through the same transition that the North had to endure, about a hundred years earlier. The industry erupted from the tracks of newly forged steel that comprised the railways interconnecting the South and brought a new sense of economic development as it tied together the nation's trade.

Works Cited

"Bibb City: Collected Lives from a Mill Town." Bibb City: Collected Lives from a Mill Town.

Columbus State University, 2 Sept. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.

“Cotton Mills and Child Labor.” Macon Telegraph [Macon] 30 Jun. 1903: 1-2. Georgia

Historical Newspapers. Web. 13 February 2015. <http://telegraph.galileo

.usg.edu/telegraph/view?docId=news/mdt1903/mdt1903-1499.xml&query=cotton% 20mills%20labor&brand=telegraph-brand>.

"Something About Macon." Macon Telegraph [Macon] 17 Sept. 1902: 6. Georgia Historic

Szdfan. "MennoDiscuss.com." • View Topic. PHPBB, 20 June 2012. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.

“The Fall River Cut.” Macon Telegraph [Macon] 11 Dec. 1897: 1-2. Georgia Historical

Newspapers. Web. 13 February 2015. http://telegraph.galileo.usg.edu/telegraph /view? docId=news/mdt1897/mdt1897-3182.xml&query=cotton%20mill%20wage&brand =telegraph-brand>.Macon Streetcar and Trolley System

After the conclusion of the Civil War in the late 1800s, the southern states had begun to go through their healing period. Slavery had been abolished, so the South had lost its source of production in a way. There were those who were angry, but on the other side of the spectrum, there were those that hoped the South would make a more economic and social advancement in order to catch up to the progress that had been occurring in the North. This ideal was known as the “New South,” promoted by those such as Henry Grady. The New South was projected throughout the south, including the little town of Macon, Georgia. There were some areas where the ideas of the New South flourished, and there were others where they were the exact opposite. For example, the trolley and streetcar systems in Macon created economic growth and an increase in social mobility, but they created hazardous conditions for those walking the streets.

The trolley and streetcar system in Macon lived up to the expectations of the New South and delivered a positive impact on the city of Macon. In the height of trolley use, Macon was projected to be a prime location to start the expansion of the rail line. It was about one hour away from Atlanta as well as Indian Springs, which was growing as a new tourist hot spot. Macon’s streetcar companies where forcing many to take note of the valuable land surround the city. They were expecting new luxury pleasure resorts to begin building throughout the major trolley stops among middle and North Georgia. The commercial and tourism rose economic development for Macon, as seen in an old article published in the Telegraph. Macon and Atlanta were combining their tracks, creating the possibility for more economic growth and an influx of people into the city. The trolleys themselves made for a “cheap and rapid mode of transportation, and [they ran] a quick schedule, so as to bring close together every section of country through which it [passed]” (“Future”). With the expansion of the rail system, jobs were becoming more accessible to Macon citizens between the building of the rails and cars, to the extra work available due to the increased tourism. Not only did the trolley system help the city of Macon economically, but it also helped increase the social mobility of people to Macon and the surrounding areas. The connection of the trolleys between Atlanta and Macon allowed for more people to make their way down, increasing the amount of tourists and new inhabitants. Those who had jobs in the city no longer had to make as costly of commutes back and forth to work each day. It was also one of the few places that forced rich and poor to share close proximity as well as mixing white and blacks together. With the expansion of trolley rails, Macon including the rest of Georgia were taking a step forward into the “New South”.

The trolley and streetcar system in Macon followed Henry Grady’s perception of the New South almost perfect economically and mobility wise, but fell short when it came to the working conditions. The addition of the trolleys helped increase the amount of people coming into the city, which eventually led to an upsurge in business for the city and settlement in and around Macon. Also, the trolleys and streetcars allowed Macon to become more accessible from other neighboring cities, thus causing a boost for mobility. On the other hand, the trolleys consisted of horrible working conditions, leading to lifelong injuries and sometimes death. People were either struck by the incoming streetcars, or electrocuted to death by working around the numerous wires. Trolleys for their positives and negatives would be one of the most important elements that would bring Macon into the New South.

Works Cited

A Double-truck Streetcar at Crumps Park in Macon. 1911. Macon. Railga. Web. 24 Feb. 2015.

<http://www.railga.com/oddend/streetrail/maconstr.html>

“ALL OVER GEORGIA.” Macon Telegraph [Macon] 16 August. 1890: 8. Georgia Historic

Newspaper. 13 Feb. 2015.

“Future of Electric Car Lines in Georgia.” Macon Telegraph [Macon] 21 Jul. 1902: 6.

Georgia Historic Newspapers. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

<http://telegraph.galileo.usg.edu/telegraph/view?docId=news/mdt1902/mdt1902

0190.xml&query=macon%20trolley&brand=telegraph-brand>.

"Justice Smith Killed By A Trolley Car." Macon Telegraph [Macon] 22 May 1903: 8. Georgia

Historic Newspapers. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

MITSI Trolley. N.d. Macon. Mta-mac. Web. 24 Feb. 2015. <http://www.mta-mac.com/mitsi.html>.

MTA trolley green and white, Downtown. Personal photograph by author. 2015.

Southern Railroad Depot. 1886. Macon. Railga. Web. 24 Feb. 2015.

<http://railga.com/Depots/macon.html>.

Streets in Downtown. 1871. Macon. Railga. Web. 24 Feb. 2015

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)